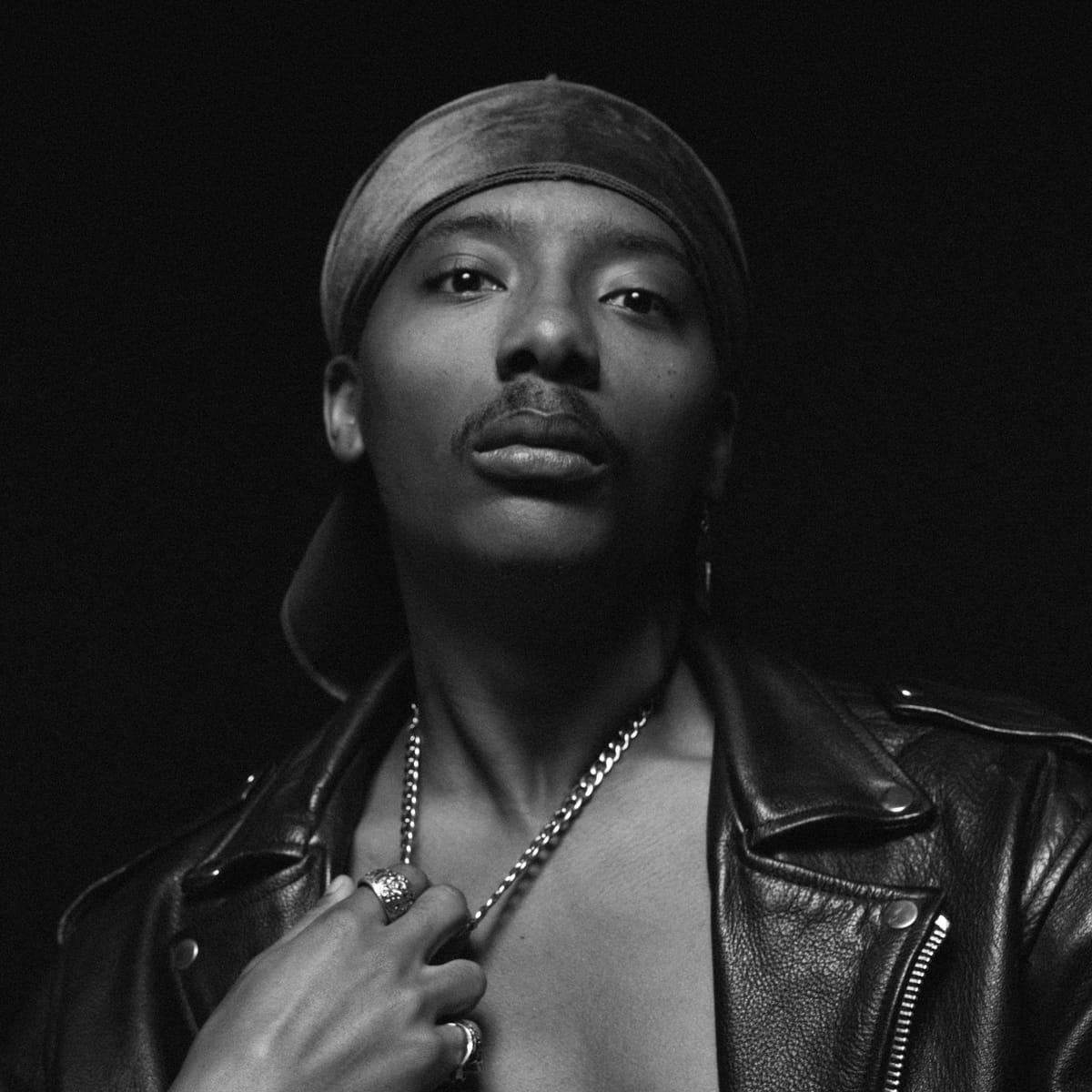

Quinton Barnes and the Black Avant-Garde

"I was asking, 'What and where is the Black avant-garde?' CODE NOIR and BLACK NOISE were both answers."

This past January, Montreal artist Quinton Barnes dropped CODE NOIR, an intricate weaving of queer rave, footwork, and R&B, all recorded in Barnes's bedroom. The album is sexual, energetic, and above all - very danceable. Then, five months later, Barnes put out BLACK NOISE, a more abstract album recorded with the backing of a full orchestra. So a little less DJ Rashad, a little more Moor Mother.

Although the albums sound very different on the surface, they're connected by more than just close release dates. “For me they always were kind of based off the same ideas,” Barnes explains, and cites the works of Saidiya Hartman, Eduardo Mendieta, and Fred Moten as academic starting points. “I was asking and trying to answer the questions: 'What and where is the Black avant-garde? Where is its energy located?' CODE NOIR and BLACK NOISE were both answers.”

These albums aren’t the first time he’s explored this topic, either. Barnes views the two as part of a spiritual trilogy; beginning with 2022's industrial-tinged For the Love of Drugs. And while last year’s HAVE MERCY ON ME might not slot into that trilogy, the ways it toys with genre still places it within the Black avant-garde conversation (notably, the album was created over three weeks after Barnes opened for acclaimed experimental hip hop artist Backxwash).

Barnes jumped on a voice call with me and together we chatted about the two albums. We had a really good talk about the ways critical theory informs his music, what people consider “cerebral” music, and of course, the Black avant-garde.

To start off - releasing two albums in a year is pretty impressive! And two totally different sounding albums, too.

Yeah, it was a lot of fun. I just felt the need to, like, get it all out.

Did you end up working on the albums at the same time?

The way I had done it was like, I finished For the Love of Drugs in 2022, and then I started CODE NOIR immediately after that. I started BLACK NOISE at the same time, and that was a whole organized process with the grant and all that.

I viewed CODE NOIR and BLACK NOISE as being in direct conversation with each other, and not just because they had been released so close together. Did you intend them to read as a dual album?

Oh, yeah, definitely. A lot of the concept for BLACK NOISE basically came out of reading a lot of critical theory, actually. Musicology, cultural criticism, and those sorts of things. I was reading a lot of Afropessimist thought and getting really into that. It got me thinking about Black experimental music and the avant-garde and its relationship to Black people and Black culture.

I had these two different ideas about where the Black experimental conversation was happening. With CODE NOIR, I was really into footwork and more regional sounds. I was interested in the idea of regional hip-hop and the energies that were coming out of that. I was really interested in footwork as a cultural form, because a lot of it was based in warehouses and these communal spaces that weren't necessarily where you'd expect them - these very underground communities that some people might consider economically or politically “left behind”. And then, often the music was developed in tandem between the producers and the dancers. So it was very physical, and the music ended up being very visceral. They’re very innovative rhythms, and it's like they're almost demanding a new type of movement in the sound itself. A lot of experimental music fans love really cerebral work (or at least, what they consider cerebral), but I thought of footwork as cerebral, because it's this sort of mind-body-music connection.

And then with BLACK NOISE, it was taking the same sort of somatic and conceptual concerns, and then doing the whole “experimental” thing, with the noise ensemble and the jazz. For me, it was two different ways of engaging with Black experimental music in 2025.

I listened to the album inspiration playlists you made for CODE NOIR and BLACK NOISE. It was so interesting to see the influences across the albums range from footwork to like, Scott Walker’s Bish Bosch.

Yeah, I love that album. I really like his late avant-garde work. Bish Bosch is just so weird. I get chills listening to that album. It's just so cool.

It took me a while to listen to it all the way through, because I would get to the fart noises and be like, “okay, I’m not in the right headspace, I’ll get back to this.”

[laughs] Yeah, it's very uncompromising. I just like the idea of, like, getting older and weirder and less comprehensible. That's how you should age.

No, I agree. Is that something you consciously think about when you make music? Do you check in with yourself and say, “hey, am I holding myself back here? Am I pushing the form as much as I want?”

I mean, not exactly - it's like a push and pull thing. I feel like it's always about, like, “Is everything I'm doing serving the music? Is this the best possible realized version of this idea?” Because while some art can be uncompromising, other times it’s like…maybe you should have compromised. [laughs] There’s a balance you have to have.

Yeah, that makes sense. And now that I think about it, it's hard to even talk about “experimental music” or even “avant-garde” – since everyone kind of has different reads on what those things are.

Well, it's so funny - I was on Reddit the other day, and I saw someone that was like, “There's someone called Lana Del Rey, this niche cult artist.” And I was like, that’s crazy! She's huge, she's in the top 100 on Spotify! I'm like, damn, I would love to be that kind of niche.

But I guess I sort of understand. It's something I laugh at, but I'm also like… I appreciate that. It helps me gauge where people are at in terms of music - like, what they'd be receptive to. You know what I mean?

Yeah, I do - and actually, on that topic, I guess CODE NOIR would be considered more “accessible” than BLACK NOISE, since one is more like a party than the other.

Yeah, but I mean, I just don't think I'm capable of holding myself to one thing. I always want to change, and I think people just pass on something if it's not for them. And I have been feeling more of the party lately, because sometimes I feel like maybe it's not worth being so publicly vulnerable and stuff.

Do you think you will lean more into the rave-inspired stuff going forward, then?

Oh, definitely. I'm still not done with that.

I know BLACK NOISE was pretty collaborative - was CODE NOIR more of a DIY thing?

Yeah, yeah, it was just me. Like, literally just me in my bedroom. I programmed it all - I make a bunch of beats all the time on the side, and I kind of just organized it and built the album from there.

And then, how did you link up with all the different collaborators on BLACK NOISE?

So it started from a tweet where I was like, “I want to work with free jazz and noise musicians.” And then Michael Duguay, who produced the album, saw my tweet and he reached out to me. He had this idea of commissioning the pianist, Edward [Enman], and he knew the other musicians, and we ended up getting the grant funding and recorded at the studio. We used Edward’s compositions as a basis for what we were going to make. It was a great crew, and everyone was, like, amazing at what they did.

Was it a lot of improvisation?

Oh, yeah, yeah, it was pretty much all improvisational.

Did you kind of let them take the reins on the instrumental aspect, or going in did you already have a good idea of where you wanted it to go?

No, we did have notes going in. We had a bit of an outline for the genesis of each track. But we were able to take it in whatever direction felt right. I think that's why there's so many different sounds and stuff all over the album. It was a lot of exploring.

And then for the final track, “Movement 7” - how did that fit in with everything? Was that suite already recorded?

Yeah, that was just one of Edward's pieces, unedited, just as it was.

I like that as a closer a lot because it switched up the energy in a really captivating way. What made you want to close out with it?

Well, Michael had an idea for the structure of how the album would work, so he was really envisioning it with the ballad ending. It ended up working well.

(...and here is where my bad connection cut the call completely, and we switched over to email...)

Looping back to what you said earlier about Afropessimist thought and critical theory - can you tell me a little more about how they inform these albums?

Both For the Love of Drugs and BLACK NOISE were born out of a multi-year obsession: a very formal, almost academic inquiry, engaging directly with thinkers like Frank Wilderson, Zakkiyah Iman Jackson, Fred Moten, Saidiya Hartman, and Jacques Attali. The central question of that record was: If the entire structure of Western thought, of "Being" itself, is fundamentally and necessarily anti-Black, then what is the true function of Black sound? My conclusion, and the one the album explores, is that Black sound, in this context, functions similar to the position of "Noise" articulated in Attali's work. BLACK NOISE, the album, is a deliberate attempt to inhabit that very noise, to deconstruct it from the inside, to treat Attali's theory as template and use it as a basis for Afropessimist inquiry. It speaks to the historically white avant-garde in a language it might understand and finds: one of rupture, of difficulty, deconstruction, explicit intellectualization, of institutional critique.

Going down this line of thinking made me see potential multifaceted points of engagement across culture. There are two quotes that inspired me during this time:

“The idea of the avant-garde is embedded in a theory of history. This is to say that particular geographical ideology, a geographical-racial or racist unconscious, marks and is the problematic out of which or against the backdrop of which the idea of the avant-garde emerges…part of what I’m after is this: an assertion that the avant-garde is a black thing and the assertion the blackness is an avant-garde thing.”

--Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition

“We inhabit a sound world built by racism. We dwell in the sound house of race. Before racism is chromocratic, it is phonocratic. The technologies of the racist self are the technologies of racializing aurality and phonology.”

--Eduardo Mendieta, The Sound of Race: The Prosody of Affect

This all influenced my thoughts on sound as a contested terrain where Black cultural work both fortifies, contests and reconfigures its relationship to the structural and ontological position of Blackness. This led to me decoupling my understanding of "noise" as the terrain of where For the Love of Drugs and BLACK NOISE intend to work, and the shift where I began to see any Black musical/cultural contribution as potential terrain for the same questions.

This led to CODE NOIR, where I decided a more potent conversation for Black avant-garde music could also occur in multiple cultural sites: the birth of the Black queer rave scene, the genesis of Chicago footwork and ghetto house, the global diasporic conversation happening within and around amapiano, gqom, deep house, baile funk, etc. I thought of these as not just "genres"; but radical and sophisticated cultural, racial and sonic technologies. I thought of the historic BLACK CODE/CODE NOIR laws in both the US and France and sought to make a musical 'Black Code' that took all these disparate scenes and utilized them as inspiration for how I imagined contemporary Black music should sound in the face of its negated ontological position.

So, with CODE NOIR, the approach was an evolution from the initial question. It was an act of re-centering, reimagining and further iteration on the initial impulse. It was an attempt to communicate similar ideas via different means.

Is the question of "what and where is the Black avant-garde" something you plan to keep exploring with your music? Are there other genres / scenes that you want to interrogate next?

100%! I don't think I've exhausted my perspective on this yet. I currently am still fixated on the same sonic palette that inspired CODE NOIR, in addition to a new interest in the many regional rap scenes that are thriving now and how I might contribute to that ongoing conversation.

Support BLACK NOISE and CODE NOIR on Bandcamp, and follow Barnes over on Instagram.